The Charles H. Wright Museum

of African American History

Pre-Reconstruction & Reconstruction (1863 - 1877)

The American Civil War took place between 1861 to 1865. Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863. Reconstruction is defined as the period after the Civil War in which seceded stated were integrated back into the Union.

“The black military role in support of the Union,” historian Steven Hahn notes, “made possible a revolution in American civil and political society that was barely on the horizon of official imagination as late as the middle of 1864 . . . a revolution that potentially extended to the redistribution of confiscated white property and the guarantee of political and civil rights for free and freed blacks.”

The Civil War firmly identified the Republican Party as the party of the victorious North and of African Americans hoping to claim full citizenship. After the war the Republican-dominated Congress forced a “Radical Reconstruction” policy on the South, which saw the passage of the 13th Amendment (ratified in 1865), 14th Amendment (ratified in 1868), and 15th Amendment (ratified in 1870) to the Constitution and the granting of equal rights to all Southern citizens.

- The 13th Amendment

-

The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1865 in the aftermath of the Civil War, abolished slavery in the United States. The 13th Amendment states: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

- The 14th Amendment

-

Ratified in 1868, The 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States—including former slaves—and guaranteed all citizens “equal protection of the laws.” One of three amendments passed during the Reconstruction era to abolish slavery and establish civil and legal rights for black Americans, it would become the basis for many landmark Supreme Court decisions over the years.

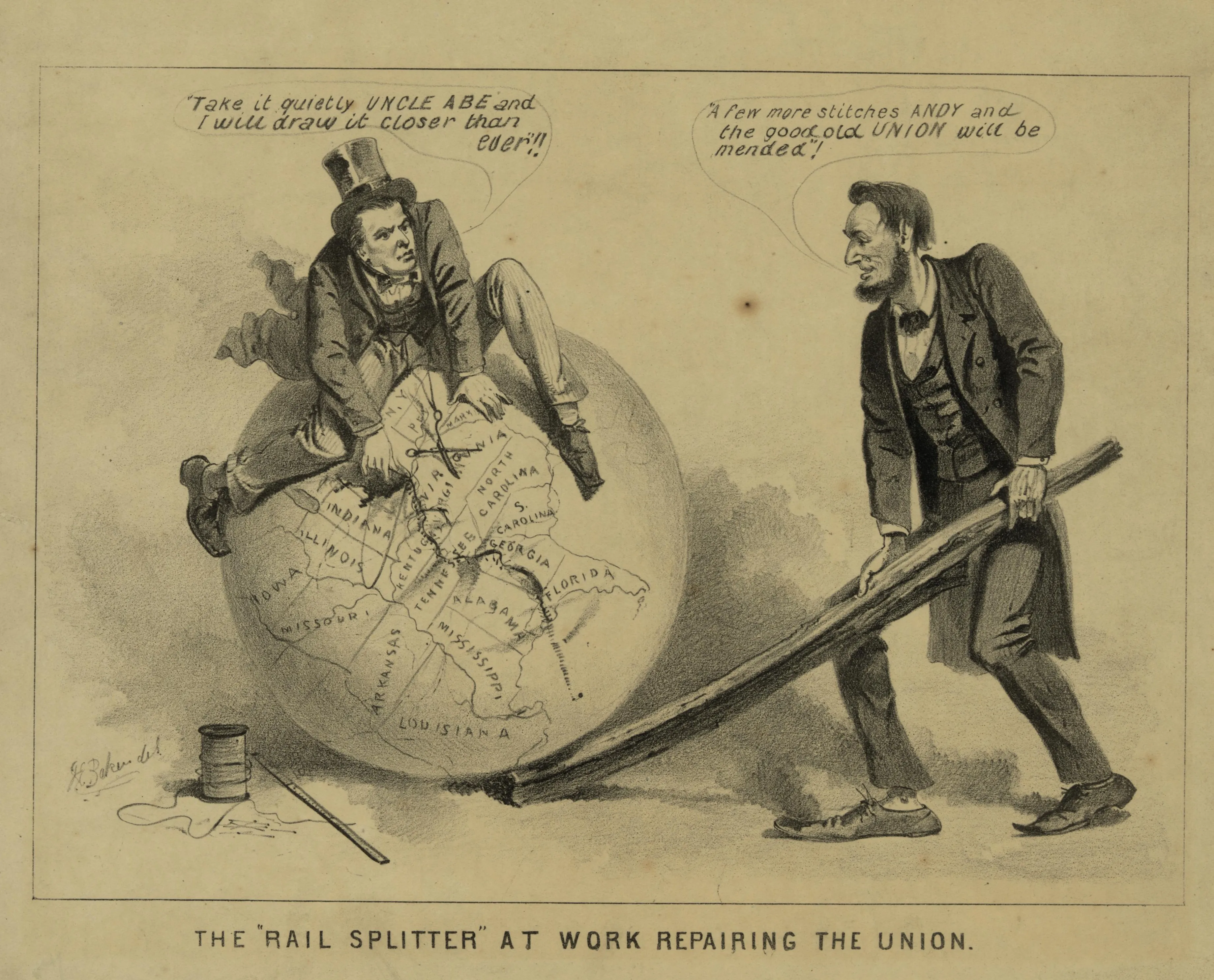

Repairing the Union

In December 1863 Lincoln announced a Reconstruction plan for Southern states, promising to recognize their governments if they pledged to support the Constitution, the Union, and to emancipate the slaves backed by at least 10 percent of the number of voters in the 1860 presidential election.

Radical Republicans backed by abolitionists and free Blacks were outraged at these procedures and put forth their own plan in the Wade–Davis Bill. It required not 10 percent but a majority of the white male citizens in each Southern state to participate in the reconstruction process, and it insisted upon an oath of past, not just of future loyalty.

Ballot or Bullet

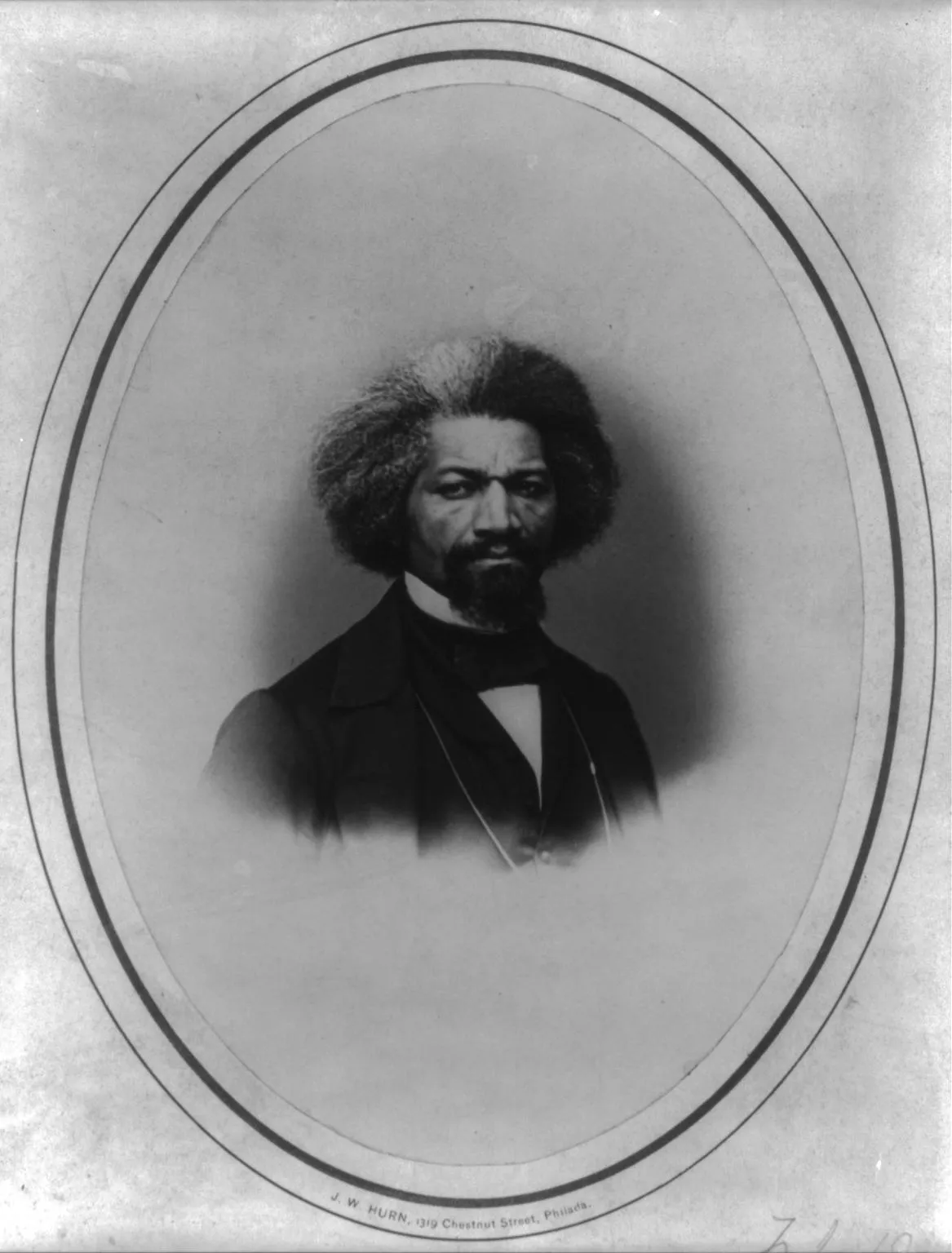

In 1867, a newspaper in Tennessee quoted Frederick Douglass as saying: “A man’s rights rests in three boxes: the ballot-box, the jury-box and the cartridge-box, and the man who is outside these boxes is in a bad box.

Let no man be kept from the ballot-box because of his color. Let no women be kept from the ballot-box because of her sex.” This theme of the ballot or the bullet is echoed over one hundred years later by activist Malcolm X. "

The Ballot or the Bullet" became one of Malcolm X's most recognizable phrases. Two thousand people – including some of his opponents -- turned out to hear him speak in Detroit.

National Equal Rights League (NERL)

Founded in Syracuse, New York in 1864, the National Equal Rights League (NERL) promoted full and immediate citizenship for African Americans. The League based its call for full citizenship as compensation for military service in the Revolutionary and Civil Wars. They argued that the sacrifices of African Americans on the battlefield entitled all black males to the ballot and all black men and women to full citizenship.

The founders of the NERL included Henry Highland Garnet, Frederick Douglass, and John Mercer Langston, among other prominent leaders. Although it began in New York, it quickly spread throughout the country immediately after the Civil War. Active local branches grew in Louisiana, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Ohio, Missouri, and especially North Carolina.

The NERL quickly became associated with Republican politics at the local and national level. Although African American men were little more than 2% of the Northern population in 1870, they nonetheless worked toward full civil rights.

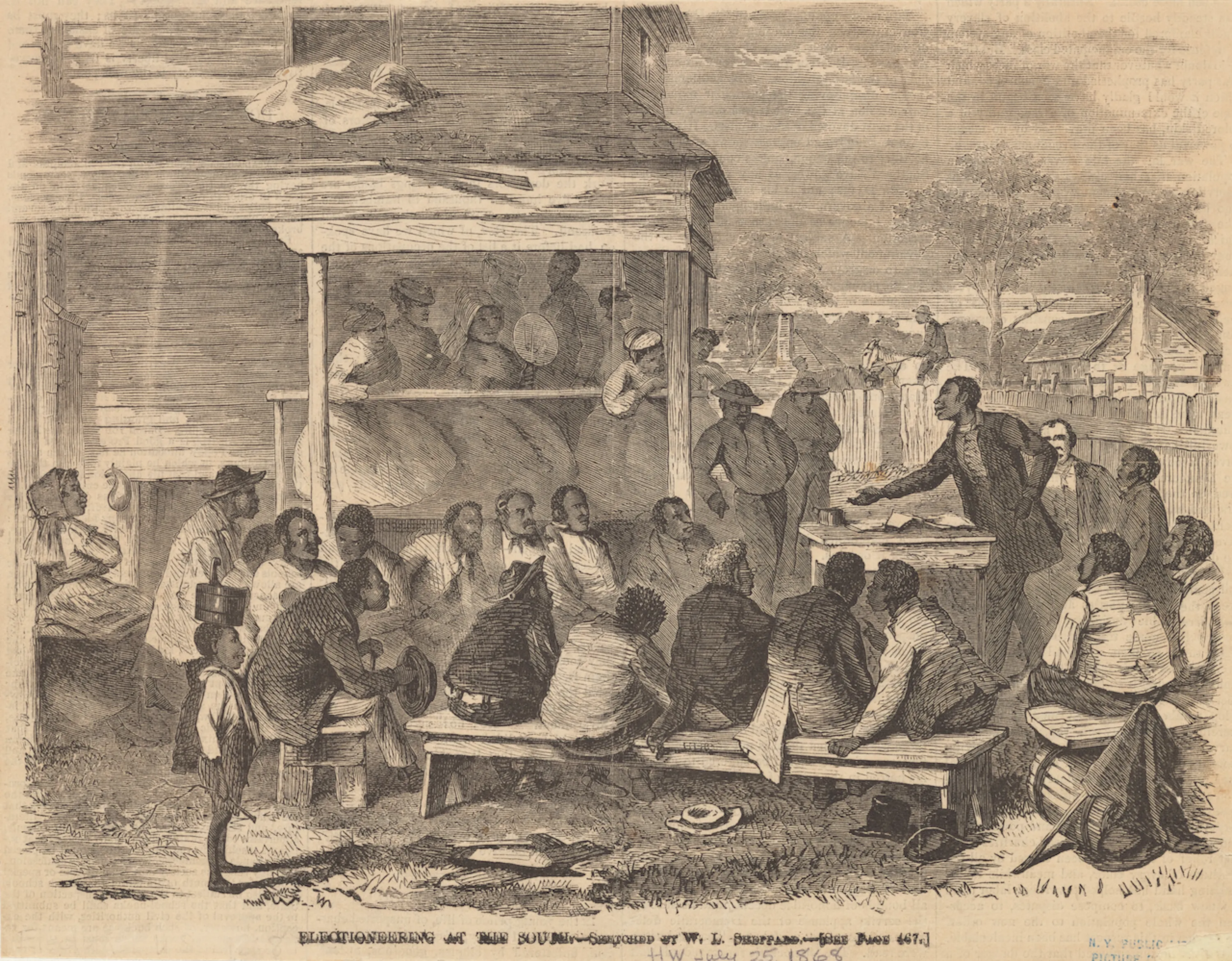

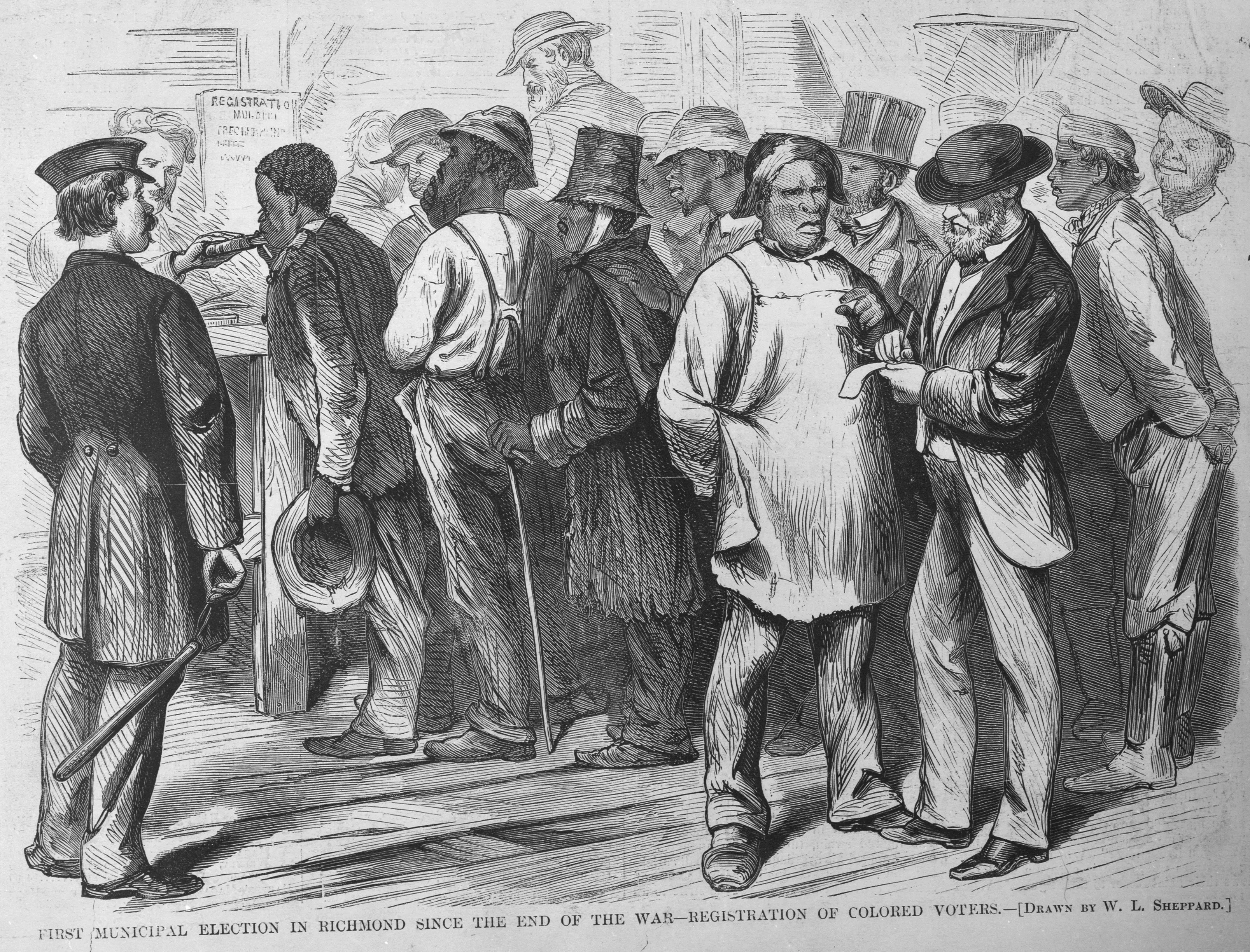

Registration

By the time the new voter registration process was completed, Blacks were a majority of the registered voters in Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, and Georgia. In South Carolina, there were nearly two Blacks registered for every white person. In every other Southern state, they held sizable and influential minorities.

Starting in Alabama in November of 1867 and ending with Texas that opened its convention in June of 1868, multiracial assemblies met in Southern state capitol buildings — most built by the labor of the enslaved — to radically alter the political and economic landscape.

Historian Lerone Bennett Jr. noted, "Although experienced men, some of them lawyers and former legislators, moved to the fore in many places, there was, in every state convention, an articulate core of common people who spoke with uncommon authority, not because they had conferred with the people, but because they were the people."

In the name of the people, these delegates fought to make Southern constitutions reflect social and economic justice. The Mississippi state convention passed a tax for the relief of needy freedmen and a resolution that would have returned property taken from freedmen if it hadn’t been vetoed by the general controlling the state.

In Alabama, a resolution passed that allowed freedmen to collect $10 a month in back pay from former masters for any work completed after January 1, 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation took effect.

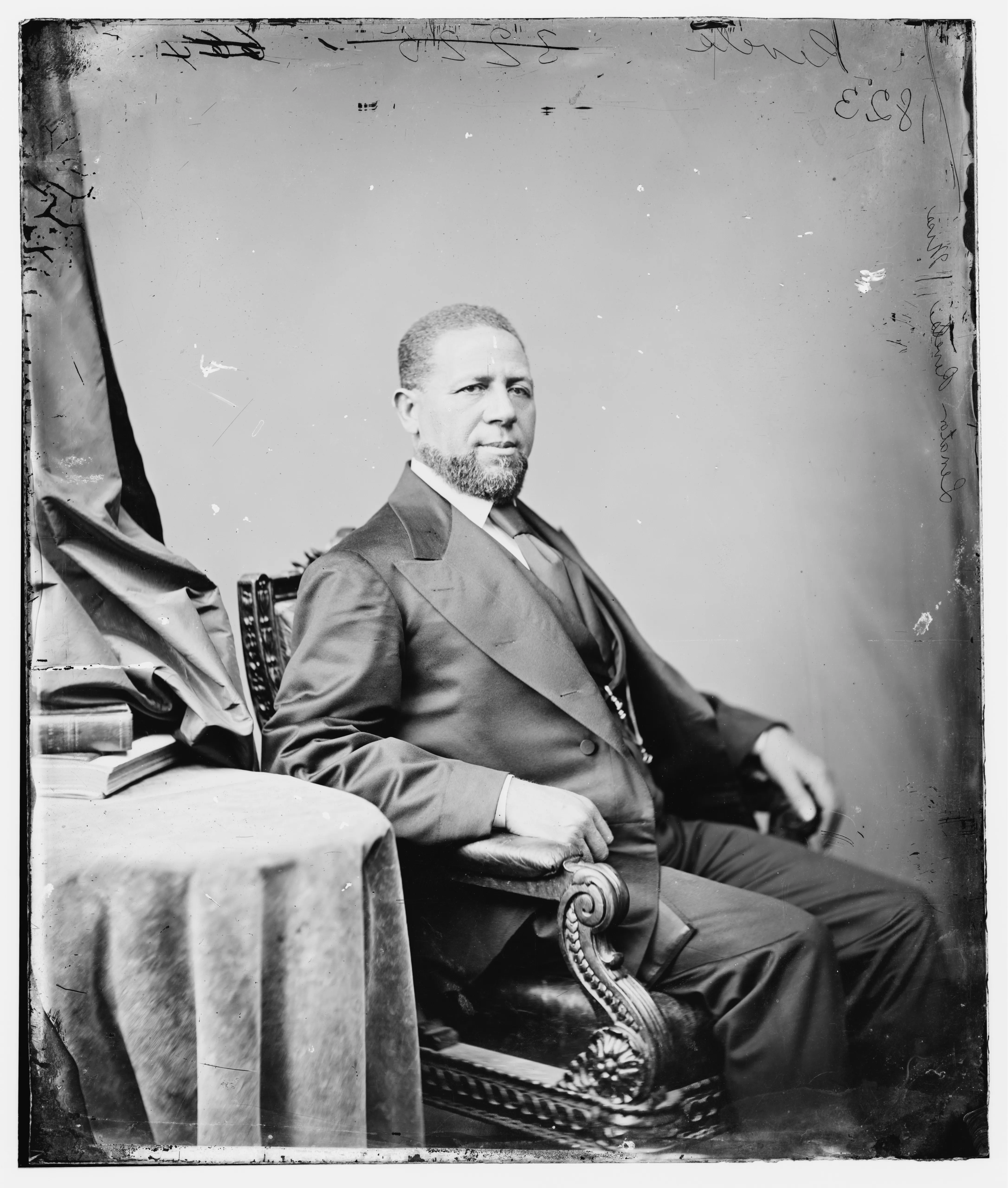

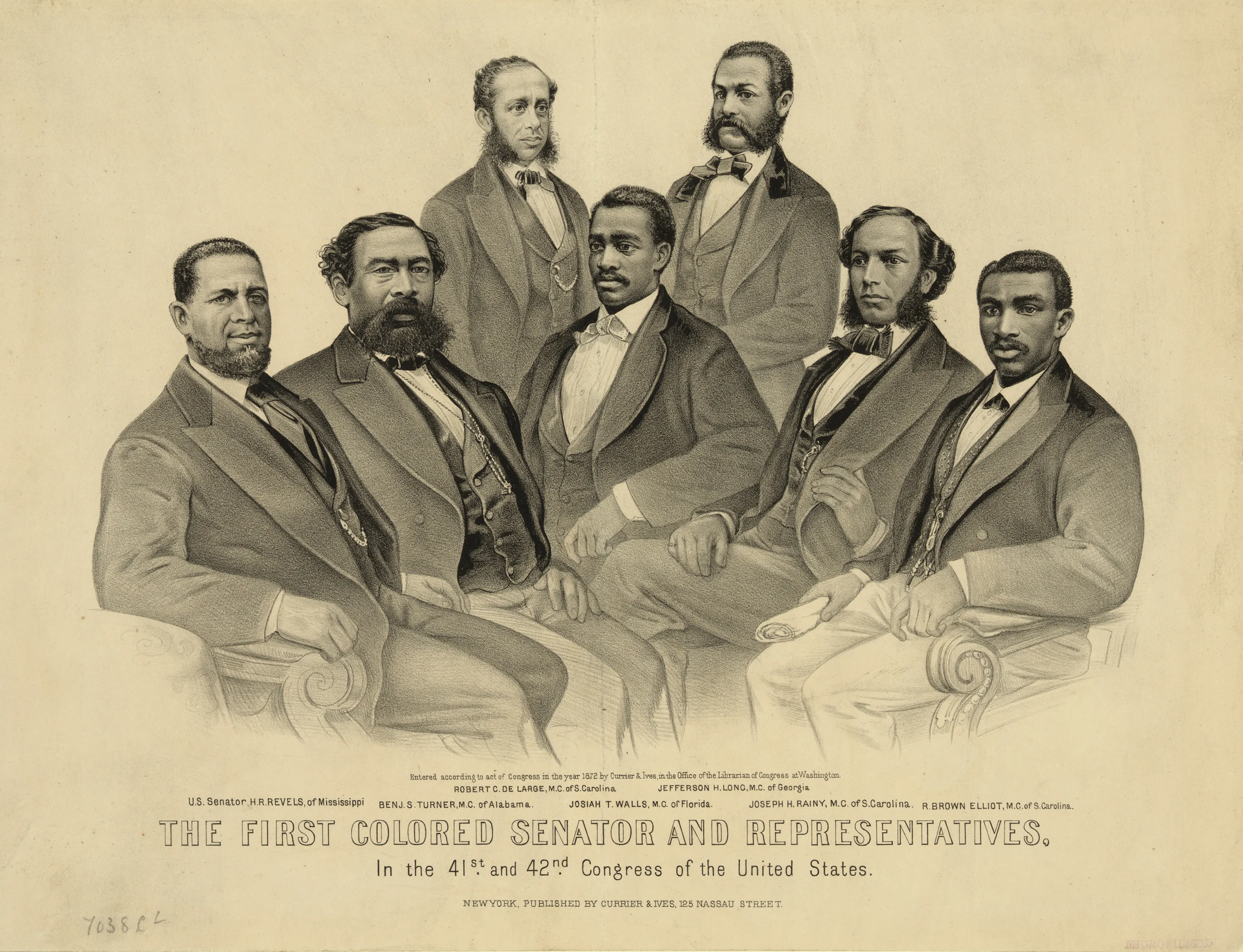

A First for the U.S. Congress

Hiram Revels became the first African American to serve in the U.S. Congress when he was elected to the United States Senate as a Republican to represent Mississippi in 1870 and 1871. Over 2000 blacks held elected office, from the local level up to U.S. Senate. 265 African American were elected delegates at state constitutional conventions (including Robert Elliott), more than 100 were former slaves, primarily in South Carolina and Louisiana.

State delegate Robert Elliott, who was born in England and represented South Carolina would also rise to Senator. Soon black representatives were helping to write new, more egalitarian state constitutions. The KKK and other white supremacy groups attacked and killed 35 black officials.

Regaining a Voice

When Mississippi rejoined the Union in 1870, former slaves made up more than half of that state’s population. During the next decade, Mississippi sent two black U.S. senators to Washington and elected a number of black state officials, including a lieutenant governor.

But even though the new black citizens voted freely and in large numbers, whites were still elected to a large majority of state and local offices. This was the pattern in most of the Southern states during Reconstruction. The Republican-controlled state governments in the South were hardly perfect.

Many citizens complained about over taxation and outright corruption. But these governments brought about significant improvements in the lives of the former slaves. For the first time, black men and women enjoyed freedom of speech and movement, the right of a fair trial, education for their children, and all the other privileges and protections of American citizenship.